Revista Portuguesa de Estomatologia, Medicina Dentária e Cirurgia Maxilofacial

SPEMD - Revista Portuguesa de Estomatologia Medicina Dentária e Cirurgia Maxilofacial | 2025 | 66 (1) | 3-9

Original research

Psychometric properties of the Scale of Oral-Health Outcomes in a Portuguese pediatric population – Exploratory study

Propriedades psicométricas da Scale of Oral Health Outcomes numa população pediátrica portuguesa – Estudo exploratório

a Universidade de Lisboa, Faculdade de Medicina Dentária, Unidade de Investigação e Ciências Orais e Biomédicas (UICOB), Lisbon, Portugal

Susana Morgado - smorgado1@edu.ulisboa.pt

Paula Faria Marques - smorgado1@edu.ulisboa.pt

Ana Coelho Canta - smorgado1@edu.ulisboa.pt

Sónia Mendes - smorgado1@edu.ulisboa.pt

Article Info

Rev Port Estomatol Med Dent Cir Maxilofac

Volume - 66

Issue - 1

Original research

Pages - 3-9

Go to Volume

Article History

Received on 08/08/2024

Accepted on 27/01/2025

Available Online on 31/03/2025

Keywords

Original Research

�

Psychometric properties of the Scale of Oral-Health Outcomes in a Portuguese pediatric population � Exploratory study

Propriedades psicom�tricas da Scale of Oral Health Outcomes numa popula��o pedi�trica portuguesa � Estudo explorat�rio

�

Susana Morgado1,* 0000-0001-5715-3946

Paula Faria Marques1 0000-0002-3117-6530

Ana Coelho Canta1 0000-0003-2419-771X

S�nia Mendes1 0000-0001-8831-5872

1 Universidade de Lisboa, Faculdade de Medicina Dent�ria, Unidade de Investiga��o e Ci�ncias Orais e Biom�dicas (UICOB), Lisbon, Portugal

�

�

Article history:

Received 8 August 2024

Accepted 27 January 2025

available online 6 march 2025

�

Abstract

Objectives: This exploratory study aimed to contribute to the validation of the Scale of Oral Health Outcomes for 5-year-old children (SOHO-5) for a Portuguese pediatric population.

Methods: This cross-sectional study included children between 5 and 7 years old. The non-probabilistic sample included a school in Lisbon. Children who agreed to participate and whose guardians signed the informed consent were included. Data collection included a questionnaire and intraoral examination for the children and a self-administered questionnaire for their guardians. The questionnaires included the Portuguese adaptation of each SOHO-5 version (children�s and guardians�). The intraoral examination included caries diagnosis according to the World Health Organization�s criteria. The study of psychometric properties included the item frequency, item-total correlation, internal consistency (Cronbach's α), and test-retest (intraclass correlation coefficient - ICC). The Mann-Whitney U-test was used to assess discriminant validity and Spearman's correlation coefficient for criteria validity. All tests used a level of significance of 5%.

Results: The sample included 60 children. Cronbach's α was 0.86 and 0.83 for the children�s and guardians� SOHO-5 versions, respectively. The test-retest demonstrated an ICC of 0.82 (children�s version) and 0.95 (total score) (p<0.01), indicating good reliability. The guardians� version showed discriminant validity, and both versions showed criteria validity (p<0.05).

Conclusions: The Portuguese adaptation of SOHO-5 showed acceptable psychometric properties. However, studies with representative and bigger samples are necessary to confirm that SOHO-5 is a reliable and valid tool to measure the impact of oral health in Portuguese pediatric children.

Keywords: Children, Oral health, Quality of life, Reliability and validity

�

Resumo

Objetivos: Este estudo explorat�rio pretendeu contribuir para a valida��o da Scale of Oral Health Outcomes for 5-year-old children (SOHO-5) numa popula��o pedi�trica portuguesa.

M�todos: Estudo transversal com crian�as entre os 5-7 anos. A amostra n�o probabil�stica compreendeu uma escola de Lisboa, sendo inclu�das as crian�as que aceitaram participar e cujos respons�veis assinaram o consentimento. A recolha de dados incluiu um question�rio e um exame intraoral �s crian�as e um question�rio autoadministrado ao respons�vel da crian�a. O question�rio inclu�a a adapta��o portuguesa de cada vers�o do SOHO-5 (da crian�a e do respons�vel). O exame intraoral incluiu o diagn�stico de c�rie segundo os crit�rios da Organiza��o Mundial de Sa�de. O estudo das propriedades psicom�tricas incluiu a frequ�ncia dos itens, a correla��o total e inter-item, a consist�ncia interna (α de Cronbach) e o teste-reteste (coeficiente de correla��o intraclasse � CCI). A validade discriminante foi estudada com o teste de U-Mann-Whitney e a de crit�rio com a correla��o de Spearman. O n�vel de signific�ncia estat�stica usado foi 5%.

Resultados: A amostra incluiu 60 crian�as. O α de Cronbach foi de 0,86 e 0,83 nas vers�es do SOHO-5 da crian�a e do respons�vel, respetivamente. O teste-reteste demonstrou um CCI de 0,82 (vers�o da crian�a) e 0,95 (pontua��o total) (p<0,01). A validade discriminante foi demonstrada na vers�o dos respons�veis e a de crit�rio em ambas as vers�es (p<0,05).

Conclus�es: A adapta��o portuguesa do SOHO-5 mostrou propriedades psicom�tricas aceit�veis, sendo necess�rios estudos em amostras maiores e representativas para confirmar a sua fiabilidade e validade na popula��o portuguesa.

Palavras-chave: Crian�as, Sa�de Oral, Qualidade de vida, Fiabilidade e validade

�

Introduction

Dental caries is considered one of the most prevalent diseases in childhood.1 Approximately 532 million children have untreated caries in deciduous teeth.2

In Portugal, dental caries is highly prevalent. The last Portuguese national study revealed a notorious 45.2% prevalence of dental decay in 6-year-old children.3 One study in the District of Lisbon reported a 26.0% prevalence in a preschool population,4 and another study carried out in Coimbra found a 30.3% prevalence in 5-year-old children.5

Untreated caries might cause difficulties in sleeping and eating and possibly affect children�s growth and development.6 Several studies have reported that children who suffer from cavitated dentin caries have lower body weight and height than those with no dental caries.7, 8 In addition, higher rates of absenteeism were found in children with untreated lesions, revealing a high negative impact on their school performance.9 Hospitalization or emergency dental visits were also reported in some severe cases.10

Dental caries significantly negatively impact children�s oral health-related quality of life (OHRQoL),11, 12 and that impact tends to increase as the disease severity worsens.11 OHRQoL is a multidimensional assessment that reflects the patient�s oral function and psychological and social aspects.13, 14 Although traditional clinical measures can express the physical condition of dental caries, they cannot reveal the disease�s psychosocial impact on the affected children.15 In addition, assessing the health-related quality of life has become essential to evaluate interventions and appropriately allocate resources for health care services.16

Different instruments were developed to measure OHRQoL in children over 6 years old,17 - 19 and, in recent years, other scales were developed specifically for children under 6 years old.20 21

Most of these instruments for young children have relied on parent proxy reports.21, 22 However, there is increasing evidence that 4�6-year-old children can reliably report information regarding their general health and quality of life.20 23 Even though the parent proxy reports have an important role in children�s OHRQoL measurement, obtaining both perspectives, if possible, has been proven better for a comprehensive view.24

The Scale of Oral Health Outcomes for 5-year-old children (SOHO-5) was developed in 2012 to measure the OHRQoL of young children using both the children�s and their guardians� reports.20 This instrument was originally developed in English in Scotland and has been cross-culturally adapted and validated in Bengali,16 Brazilian Portuguese,25 Chinese,26 Indonesian,27 Persian,28 and Spanish.29 These studies demonstrated that SOHO-5 is a simple measure for these children, can discriminate between groups with different caries severity, and confirms satisfactory psychometric properties in various cultures.

The present exploratory study aims to analyze the psychometric properties of the Portuguese version of SOHO-5 in a Portuguese pediatric population.

Material and Methods

This exploratory cross-sectional study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Dental Medicine of the University of Lisbon (reference: 202326). The target population was children between 5 and 7 years old from a school in Lisbon, Portugal, and their guardians. The school was selected by convenience and had 90 children. The sample consisted of all children from the selected school aged between 5 and 7 years old who collaborated and agreed to participate in the study and whose guardians signed the informed consent. Participant�s privacy and data confidentiality were preserved.

Data were collected between March and April 2023 by na interview and intraoral examination of the participating children, as well as a self-administered questionnaire to the guardians. The children�s interviews were conducted in the school and included the Portuguese adaptation of the children�s SOHO-5 version.25

A single experienced dentist performed the dental examinations of the participant children in a classroom. Children were seated next to the window, and plaque and food debris were removed with a cotton bud. A 0.5-mm ball-ended community periodontal index probe, a dental mirror, and artificial LED illumination were used for the examination. Dental caries experience was recorded by the number of decayed, missing (due to caries), and filled deciduous teeth (dmft), following the World Health Organization criteria.30 Cross-infection control procedures were strictly followed.

The guardian�s questionnaire was self-administered and distributed with the help of the educators. This questionnaire was accompanied by a concise description of the study, outlining its goals and methods, as well as the informed consent.

The documents were returned to the school and collected by the study investigators. The questionnaire included the Portuguese adaptation of the guardian�s SOHO-5 version.25

The SOHO-5 consists of a self-reported children�s version and a self-administered guardians� version. Both versions contain seven items. In the children�s report, the items are difficulty in eating, drinking, speaking, playing, sleeping, and avoiding smiling due to pain and due to appearance. All items are rated on a 3-point scale (no = 0, a little = 1, and a lot = 2).

The items in the guardians� report comprise difficulty in eating, playing, speaking, sleeping, affected self-confidence, and avoiding smiling due to pain and due to appearance. The items are rated on a 5-point scale (not at all = 0, a little = 1, moderately = 2, a lot = 3, a great deal = 4, and do not know = 5). The total SOHO-5 score is the sum of all items� rates, including both the children�s and guardians� versions. The score of each SOHO-5 version (children�s and guardians�) can also be calculated individually. A higher score indicates a more significant negative impact on the child and, therefore, a poorer OHRQoL.20

The Portuguese adaptation of the SOHO-5 questionnaire applied in this study was adapted from the Brazilian Portuguese SOHO-525 Small language adaptations were made considering the Portuguese local culture. This adaptation�s conceptual and item equivalence was previously revised and evaluated by an expert panel. The panel consisted of three dentists with research experience: two Portuguese and one Brazilian.31

Duplicate examinations were randomly performed 14 days after the initial examination in around 20% of the children (n=11) to study intra-examiner and test-retest reliability.

The data collected were analyzed using Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS version 26.0). Descriptive analysis included the calculi of absolute and relative frequencies of all variables and the mean and standard deviation (SD) of numerical variables. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test assessed the normal distribution. Psychometric properties included the item frequency, item-total correlation, internal consistency (Cronbach�s α), and test-retest (intraclass correlation coefficient - ICC). The Mann-Whitney U-test assessed the discriminant validity by comparing the SOHO-5 scores of the children with and without dental caries experience. The validity of the criteria was studied using Spearman�s correlation coeficiente between SOHO-5 and deciduous dental caries experience. All tests used a level of significance of 5%.

Results

All children from the selected school who met the inclusion criteria (n=69) were invited to participate in the study. However, nine of the potential participants did not return the informed consent. Thus, the final sample included 60 children- guardian pairs, with an 87% participation rate, who underwent all study procedures (questionnaire, interview, and oral examination).

Most children participants were female (56.7%) and 5 years old (58.3%). The children�s mean age was 5.4 years old (SD=0.5). About three-quarters of the sample (76.7%) brushed their teeth at least twice daily, and 81.7% had already had an oral health appointment. Caries prevalence in deciduous dentition was 28.3% (n=17), and the mean dmft was 1.17 (SD=2.13).

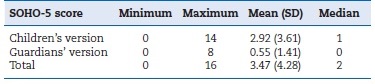

The SOHO-5 total score ranged from 0 to 16 with a mean of 3.47 (SD=4.28). Individually, the guardians� SOHO-5 scores ranged from 0 to 8, with a mean of 0.55 (SD=1.41), and the children�s SOHO-5 scores ranged from 0 to 14, with a mean of 2.92 (SD=3.61) (Table 1).

�

Table 1. Mean and standard deviation (SD), median, maximum, and minimum values of the SOHO-5 scores.

�

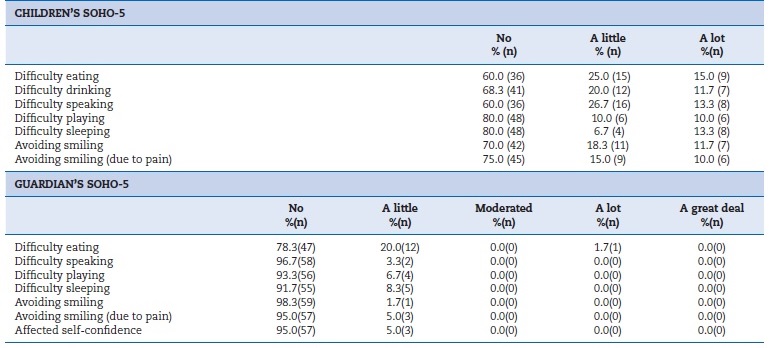

More than 66.7% of the children and 26.7% of the guardians reported at least one oral impact on OHRQoL (SOHO-5 score>0 in at least one item). The items reported by children as having the most negative impact on OHRQoL were �Difficulty eating� and �Difficulty speaking.� In turn, �Difficulty eating� had the most negative impact on OHRQoL in the guardians� version (Table 2). There were no missing values in either SOHO-5 version.

�

Table 2. Frequencies of items in the children�s SOHO-5 reports and guardians� SOHO-5 reports.

�

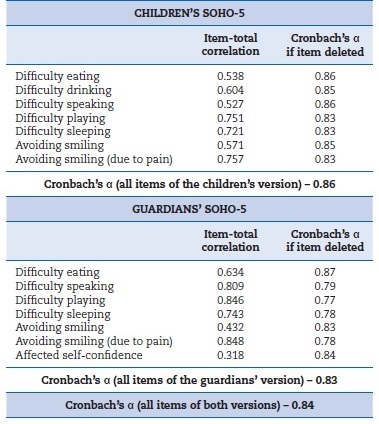

Table 3 presents the item-total correlation and the consistency analysis. The items with the lowest values of correlation were �avoiding smiling� (0.43) and �affected self-confidence� (0.32) in the guardians� version, and �difficulty in speaking� (0.53) in the children�s version. No item led to a significant increase in Cronbach�s α when eliminated. The Cronbach�s α coefficients considering all the items were 0.86 and 0.83 for the children�s and guardians� versions, respectively. The Cronbach�s α of all items of both versions was 0.84 (Table 3).

�

Table 3.Item-total correlation and internal consistency analyses of the SOHO-5 Portuguese adaptation (children�s and guardians� versions).

�

The test-retest demonstrated an ICC of 0.82 for the children�s SOHO-5 reports and 0.95 for the SOHO-5 total score (p<0.001). ICC for the guardians� SOHO-5 reports could not be calculated due to a lack of data variability.

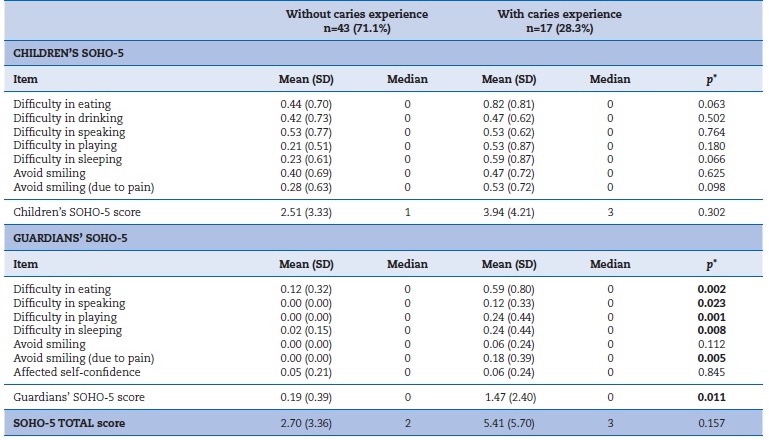

The discriminant validity was demonstrated in several items (p<0.05) of the guardians� SOHO-5 reports and the respective scores but could not be shown in the children�s SOHO-5 reports. Although the values of the items on the children�s SOHO-5 version did not show statistically significant differences, two of the items were close to the statistical decision value: �difficulty eating� (p=0.063) and �difficulty sleeping� (p=0.066) (Table 4).

�

Table 4. Discriminant validity for the Portuguese adaptation of SOHO-5 (children�s and guardians� versions).

*Mann-Whitney U-test.

Values in bold are statistically significant.

�

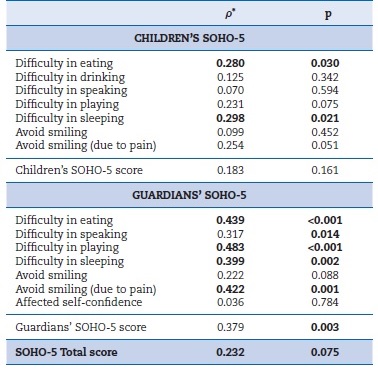

The criteria validity revealed a significant correlation (p<0.05) between some items in both versions of the SOHO-5, but more evident in the items of the guardians� version (Table 5).

�

Table 5. Criteria validity for the Portuguese adaptation of SOHO-5 (children�s and guardians� versions).

*Spearman�s correlation coefficient.

Values in bold are statistically significant.

�

Discussion

Oral health can strongly impact the OHRQoL of children and their families. This impact might not be just physical but also social, psychological, and financial.14 The SOHO-5 was culturally validated to assess that impact in various populations,25 29 but was never applied in a Portuguese pediatric population.

Having culturally valid versions of instruments in diferente languages is crucial to obtaining reliable and comparable data.

This exploratory study aims to contribute to SOHO-5 validation in the Portuguese population using a non-probabilistic small sample.

Despite its small sample, the study adhered to a common guideline of having a number of participants for validation at least equal to the number of options for each statement in each of the scale�s items. Since the SOHO-5 has seven items and a maximum of five response options per item, the sample size should be at least 35 individuals. The study sample also followed the additional recommendation to include an extra 20% of participants besides that minimum number.32

The SOHO-5 scores found in this study compare differently to others. The Brazilian study found a slightly lower mean score of 2.45 for the children�s SOHO-5 reports and a higher score of 3.67 for the guardians� SOHO-5 reports.25 In the Chinese study, the mean SOHO-5 score was also higher (1.20) in the guardians� reports and lower in the children�s reports (1.60).26 Coherently, the original Scottish study reported a mean score of the children�s SOHO-5 reports of 1.38.20 In turn the Indonesia validation study found a score similar to the present study for the children�s SOHO-5 reports (2.86) but a higher score for the guardians� SOHO-5 reports (1.53).27 Thus, the SOHO-5 scores found in the literature are very variable, possibly due to the differences in the populations� characteristics regarding oral health diseases, health literacy, oral health behaviors, and other relevant characteristics that can impact OHRQoL.

The caries prevalence in this study was 28.3% in deciduous dentition. These results were lower than those obtained by the Brazilian study (44.6%)25 and the Chinese study (53.0%).26 Other studies27,28 reported even higher caries prevalence, which may indicate sociodemographic differences in the populations studied, such as socioeconomic status, education qualifications, and access to health care. Dental caries in preschool children negatively impact the OHRQoL, and children with caries have reported twice the impact than children with no caries.12

Similar to the Scottish,20 Chinese,26 and Bengali16 adaptations of the SOHO-5, the item that demonstrated the highest impact in our study was �difficult in eating,� revealing a higher relevance of the functional domain. This result is expected in young children since understanding and regulating emotions are complex processes that require children to become more aware of their internal world and are linked to their cognitive development later in childhood.20

The most frequent answer in all scale items was �No,� which was quite notorious in the guardians� reports. Studies carried out exclusively in community populations and young children, like this one, usually show a response distribution more centered on responses with lower scores,26, 27 especially in populations that are not deprived and have a moderate prevalence of dental caries. Therefore, as expected, the presente study has a pattern of responses with lower scores compared to studies conducted in healthcare facilities, like the Brazilian25 and the Bengali16 studies.

Considering the psychometric analysis of the scale, the non-redundancy of the items was verified, with all the items moderately correlated with each other.31

The item-total correlation measures how well each item of an instrument correlates with the total score of all items.

High item-total correlations indicate that the items are consistente with the overall measure and contribute meaningfully to the total score. Conversely, low item-total correlations suggest that some items may not align well with the overall target construct and may require revision or removal to improve the questionnaire�s reliability and validity. In the children�s version, the item-total correlation verified that all items were moderately related. In the guardians� version, the item �affected self-confidence� had the lowest value (0.32), below the reference values 0.4-0.7,31 but is considered acceptable.

The scale showed a good reliability analysis with good internal consistency. The Cronbach�s α values were 0.86 for the children�s version and 0.83 for the guardian�s version. These results indicate a high level of internal consistency for both versions of the instrument, suggesting that the items within each version are reliable and measure the underlying construct.

Other studies demonstrated a wide variation in the internal consistency of the SOHO-5, ranging between 0.67 in the Persian guardian�s SOHO-5 version28 and 0.90 in the Brazilian guardian�s SOHO-5 version.25 Similar values of internal consistency were found in the Indonesian27 and Bengali16 SOHO-5 adaptations, but higher Cronbach�s α values were found in the Brazilian one.25

The Cronbach�s α value was analyzed when each item was removed, and none of the items showed a significant value increase, indicating that all items contribute to the overall reliability of the scale. The other parameter of reliability analysis was the temporal stability of the instrument.

The test-retest demonstrated an ICC of 0.82 for the children�s version and 0.95 for the total score. These results indicate excellent reliability for the total score and good reliability for the children�s version,31 suggesting that the questionnaire produces consistent results over time. This stability is crucial as it confirms that the instrument is reliable and can be used to accurately track changes or trends in the target constructs rather than being influenced by random or external factors.

Only the guardian�s version of SOHO-5 allowed distinguishing between children with or without caries experience.

The SOHO-5 scores were higher in the children who experienced dental caries, indicating an impact of the disease on OHRQoL. The Brazilian,25 Chinese,26 Indonesian,27 Persian,28 and Spanish 29 studies demonstrated good discriminant validity in both the children�s and guardians� versions.

The criteria validity showed a significant correlation between the SOHO-5 values and the dmft, but only in some scale items. This significant correlation was weak for the items in the children�s SOHO-5 version and reasonable for those in the guardian�s SOHO-5 version.33

Clinical measures, such as the dmft, focus on objective and observable aspects of oral diseases and do not always entirely reflect the psychosocial impact that oral health can have on people�s lives. Therefore, most validation studies use other variables to analyze the construct validity of scales like the SOHO-5, namely measures that allow collecting perceptions and experiences reported by guardians about their child�s oral health.25, 26, 28 It would be interesting to include this variable in the guardian�s questionnaire in future studies.

The present study pioneered in offering relevant information and contributing to validating the Portuguese adaptation of the SOHO-5, exploring the impact of oral problems on children and their families. Since the study sample was non-probabilistic and small, external validation of the results is not possible. Future studies with large and representative samples are needed to confirm the reliability and validity of SOHO-5 in a Portuguese population.

Conclusions

The SOHO-5 showed good internal consistency and good test-retest reliability. The discriminant validity was acceptable and was only found in the guardian�s reports. The criteria validity was also acceptable for the guardians� reports, but a significant weak correlation was found for the children�s reports.

The instrument is promising to measure OHRQoL in young Portuguese children, but more studies are necessary.

�

References

1. Chen KJ, Gao SS, Duangthip D, Lo ECM, Chu CH. Prevalence of early childhood caries among 5-year-old children: A systematic review. J Investig Clin Dent. 2019;10:e12376.

2. GBD 2017 Oral Disorders Collaborators, et al. Global, regional, and national levels and trends in burden of oral conditions from 1990 to 2017: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease 2017 study. J Dent Res. 2020;99:362-73.

3. Calado R, Ferreira CS, Nogueira P, Melo P. Caries prevalence and treatment needs in young people in Portugal: the third national study. Community Dent Health. 2017;34:107-11.

4. Mendes S, Bernardo M. Cárie precoce da infância nas crianças em idade pré-escolar do distrito de Lisboa (critérios International Caries Detection and Assessment System II). Rev Port Estomatol Med Dent Cir Maxilofac. 2015;56:156-65.

5. Pereira J, Caramelo F, Soares AD, Cunha B, Gil A, Costa A. Prevalence and sociobehavioural determinants of early childhood caries among 5-year-old Portuguese children: a longitudinal study. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent. 2021;22:399-408.

6. Ortiz F, Tomazoni F, Oliveira M, Piovesan C, Mendes F, Ardenghi T. Toothache, associated factors, and its impact on oral health-related quality of life (OHRQoL) in preschool children. Braz Dent J. 2014;25:546-53.

7. Li L, Wong H, Peng S, McGrath C. Anthropometric measurements and dental caries in children: a systematic review of longitudinal studies. Adv Nutr. 2015;6:52-63.

8. Acs G, Shulman R, Ng MW, Chussid S. The effect of dental rehabilitation on the body weight of children with early childhood caries. Pediatr Dent. 1999;21:109-13.

9. Neves ÉTB, Firmino RT, Perazzo MF, Gomes MC, Martins CC, Paiva SM, et al. Absenteeism among preschool children due to oral problems. J Public Health. 2016;24:65-72.

10. Allareddy V, Nalliah RP, Haque M, Johnson H, Rampa SB, Lee MK. Hospital-based emergency department visits with dental conditions among children in the United States: nationwide epidemiological data. Pediatr Dent. 2014;36:393-9.

11. Nora �D, Rodrigues CS, Rocha RO, Soares FZM, Braga MM, Lenzi TL. Is Caries Associated with Negative Impact on Oral Health-Related Quality of Life of Pre-school Children? A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Pediatr Dent. 2018;40:403-11.

12. Zaror C, Matamala-Santander A, Ferrer M, Rivera-Mendoza F, Espinoza-Espinoza G, Mart�nez-Zapata MJ. Impact of early childhood caries on oral health-related quality of life: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Int J Dent Hyg. 2022;20:120-35.

13. Bennadi D, Reddy C. Oral health related quality of life. J Int Soc Prev Community Dent. 2013;3:1-6.

14. Coelho M, Bernardo M, Mendes S. Oral Health-Related Quality of Life in Celiac Portuguese Children: a cross-sectional study. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent. 2023;24:759-67.

15. Duangthip D, Gao SS, Chen KJ, Lo ECM, Chu CH. Oral health-related quality of life and caries experience of Hong Kong preschool children. Int Dent J. 2020;70:100-7.

16. Mishu MP, Watt RG, Heilmann A, Tsakos G. Cross cultural adaptation and psychometric properties of the Bengali version of the Scale of Oral Health Outcomes for 5-year-old children (SOHO-5). Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2021;19:46.

17. Gherunpong S, Tsakos G, Sheiham A. Developing and evaluating an oral health-related quality of life index for children; the CHILD-OIDP. Community Dent Health. 2004;21:161-9.

18. Jokovic A, Locker D, Stephens M, Kenny D, Tompson B, Guyatt G. Measuring parental perceptions of child oral healthrelated quality of life. J Public Health Dent. 2003;63:67�72.

19. Varni JW, Seid M, Kurtin PS. PedsQL 4.0: reliability and validity of the Pediatric Quality of Life Inventory version 4.0 generic core scales in healthy and patient populations. Med Care. 2001;39:800-12.

20. Tsakos G, Blair YI, Yusuf H, Wright W, Watt RG, Macpherson LM. Developing a new self-reported scale of oral health outcomes for 5-year-old children (SOHO-5). Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2012;10:62.

21. Pahel BT, Rozier RG, Slade GD. Parental perceptions of children�s oral health: the Early Childhood Oral Health Impact Scale (ECOHIS). Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2007;5:6.

22. Upton P, Lawford J, Eiser C. Parent�child agreement across child health-related quality of life instruments: a review of the literature. Qual Life Res. 2008;17:895�913.

23. Barbosa T, Gavi�o M. Oral health-related quality of life in children: Part I. How well do children know themselves? A systematic review. Int J Dent Hygiene. 2008;6:93�9.

24. Pickard A, Knight S. Proxy evaluation of health-related quality of life: a conceptual framework for understanding multiple proxy perspectives. Med Care. 2005;43:493�9.

25. Abanto J, Tsakos G, Paiva SM, Goursand D, Raggio DP, B�necker M. Cross-cultural adaptation and psychometric properties of the Brazilian version of the scale of oral health outcomes for 5-year-old children (SOHO-5). Health Qual Life Outcomes. 2013;11:16.

26. Gao SS, Chen KJ, Duangthip D, Chu CH, Lo ECM. Translation and validation of the Chinese version of the scale of oral health outcomes for 5-year-old children. Int Dent J. 2020;70:201-7.

27. Rachmawati YL, Pratiwi AN, Maharani DA. Cross-cultural Adaptation and Psychometric Properties of the Indonesia Version of the Scale of Oral Health Outcomes for 5-Year-Old Children. J Int Soc Prev Community Dent. 2017;7(Suppl 2):S75-S81.

28. Asgari I, Kazemi E. Cross-Cultural Adaptation of Persian Version of Scale of Oral Health Outcomes for 5-Year-Old Children. J Dent (Tehran). 2017;14:48-54.

29. Abreu-Placeres N, Garrido LE, F�liz-Matos LE. Cross-Cultural Validation of the Scale of Oral Health-Related Outcomes for 5-Year-Old-Children with a Low-Income Sample from the Dominican Republic. J Int Soc Prev Community Dent. 2017;7:84-9.

30. World Health Organization. Oral health surveys: Basic Methods (5th edition). World Health Organization, Geneve, 2013.

31. Hill, MM, Hill A. Investiga��o por question�rio (2.� edi��o). S�labo, Lisboa, 2012.

32. Hair J, Gabriel M, Silva D, Junior S. Development andvalidation of attitudes measurement scales: fundamental and practical aspects. RAUSP Manag J. 2019;54:490-507.

33. Akoglu H. User�s guide to correlation coefficients. Turk J Emerg Med. 2018;18:91-3.

�

Susana Morgado

E-mail address: smorgado1@edu.ulisboa.pt

�

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Susana Morgado: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Validation, Resources, Writing � original draft. Ana Coelho Canta: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Writing � review & editing. Paula Faria Marques: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Writing � review & editing. S�nia Mendes: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Methodology, Supervision, Validation, Writing � review & editing.

�

Conflict of interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

�

Ethical disclosures

Protection of human and animal subjects. The authors declare that no experiments were performed on humans or animals for this study.

Confidentiality of data. The authors declare that no patient data appear in this article.

Right to privacy and informed consent. The authors have obtained the written informed consent of the patients or subjects mentioned in the article. The corresponding author is in possession of this document.

�

� 2025 Sociedade Portuguesa de Estomatologia e Medicina Dent�ria. Published by SPEMD.

This is an open access article under the CC BY-NC-ND license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).